I am Curious/Yellow (Prothonotary Warbler –

Trinity National Wildlife Refuge)

As I posted recently, I’m just coming off a month and a half

of nearly nonstop bird-ery, spent hacking my way through swamps, forests,

prairie, and beaches[i] in pursuit of tiny feathered creatures .

I’m hiding, lol! You totes

can’t see me! (Magnolia Warbler-High Island)

While hundreds of species migrate through the upper Texas

Gulf Coast (UTC) during spring, the undeniably largest draw for birdwatchers are

the Warblers[ii].

The boringly bland textbook definition[iii]

for a warbler is a member of a species belonging to “group of small,

often colorful, passerine birds which

make up the family Parulidae”. This

is a fairly useless definition for encapsulate the sheer

delight-nearing-obsession some birdwatchers experience in sighting these birds.

In most birdwatchers’ hierarchies, warblers are comfortably ensconced at the

top, secondary only to “anything I haven’t seen yet”[iv]. I think, like many things in life, the draw is

based on some mix of novelty, rarity, and the collecting instinct[v].

While it’s amazing to me that five inches of bird can hurl itself nonstop

across the Gulf of Mexico, it’s even more amazing to me how big a deal they

become when they arrive, and what millions in dollars in revenue spring from

the folks who flock to see them. The Coast pins a lot of hopes and dreams of

all kinds on these little feathered backs[vi].

I can handle the

pressure, I’m a ninja! (Hooded Warbler, Quintana)

There are over 35 species of Warblers that one can reliably

expect to see on the UTC during spring, so there’s plenty of fodder to keep the

collectors going. It all happens in a pretty short time frame, so frenzy

ensues. Regardless, there is something innately cool about getting to share

real space with some form of life you don’t get to encounter all the time. While

they’re all related, it’s interesting to see how different the characters of

the different species are. Black-throated Greens are inquisitive, and will land

on shoes and shoulders. Ovenbirds spend more time running on the ground than in

the air. Parulas are incredibly territorial. Black-and-white’s spend a lot of

time upside down on branches, comically looking for insects. Redstarts are

attention junkies. Hooded Warblers skulk about in their little ninja hood head

plumage. And so on. These differences are why simply checking off a bird on a

list is not interesting to me. It’s the observations that make the experience.

The observed becomes the

observer (Black-throated Green Warbler, Lafitte’s Cove)

Warblers are the epitome of why photographing birds is a bit

of a fool’s errand. They are small (~5”), they are often seen from moderate

distances, and they don’t stand still. I have met more than one photographer in

the field whose lenses could easily be cashed in for a car. Or three. I like

the challenge, though it has to be tempered with patience[vii].

Unless one has the patience to wait at a drip[viii]

for indeterminate periods of time, it can be hit or miss. That being said, it’s

nice when the heavens align and you get a decent shot. The heavens don’t align for me very often.

Heavens Asunder. (a few

of the many, many blurry, unfocused, or missed shots)

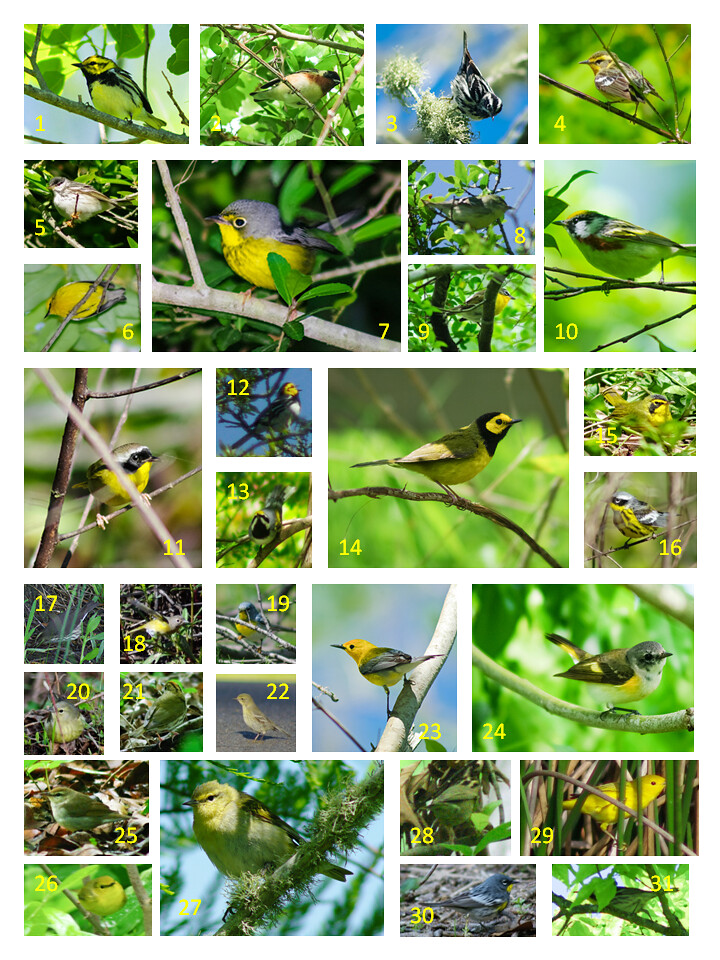

Results

As much as I poke a little good-natured fun at the obsession

with warblers, I have to admit I’ve been keeping track this season[ix].

Throughout my springtime wanderings I managed to photograph 31 species of warblers[x],

6 of which I had never seen in the

wild before, let alone photographed.

So here, in all their tiny glory, are 155 inches[xi]

of spring:

Warblers, from top: 1)

Black-throated Green, 2) Bay-breasted, 3) Black-and-White, 4) Blackburnian, 5)

Blackpoll, 6) Blue-winged, 7)Canada, 8) Cerulean, 9) Yellow-Breasted Chat, 10)

Chestnut-sided, 11) Common Yellowthroat, 12) Golden-cheeked, 13) Golden-winged,

14) Hooded, 15) Kentucky, 16) Magnolia, 17) Northern Waterthrush, 18)

Nashville, 19) Northern Parula, 20) Orange-crowned, 21) Ovenbird, 22) Pine, 23)

Prothonotary, 24) American Redstart, 25) Swainson’s, 26) Wilson’s, 27) Tennessee,

28) Worm-eating, 29) Yellow, 30) Yellow-rumped, 31) Yellow-throated.

NOTES

[i]

Ok, one doesn’t technically “hack” one’s way through a beach. Please insert a

sufficiently strenuous sounding verb of your choice.

[ii]

In this context, referring to the New World/”Wood” Warblers. They do, in fact

warble.

[iii]

If your textbook happens to be Wikipedia. Which sounds like a joke, but when

you think about it, is probably closer to a universal truth than we're likely

comfortable admitting.

[iv]

Personally, I favor the raptors. I have nothing against warblers, but other

than their vibrant coloration and relative rarity, they don’t really do

anything amazing. Conversely, they are notoriously hard to photography well

given their size and general skittishness. Raptors are, on the average, finely

honed killing machines who don’t need to count the number of f^%&s they

give, because no one needs to count to 0. They are bigger and easier to

photograph from a distance. Also, some raptors eat small passerine birds like

warblers, so, natural selection has already weighed in on this.

[v] The latter seems

to be an especially potent motivating factor. During the high period of

migration, some birdwatchers seem almost obsessed with the drive to see as many

as they can in one period of time. It’s like Pokemon for retirees.

[vi] That being

said, it is somewhat heartening in these jaded times to see someone’s eyes

light up, sans irony, by as simple a thing as a small bird.

[vii] When you think

about it, the odds of seeing any given species are really whacked out. While

millions of birds migrate across the Gulf, they’re pretty darn small, and when

they hit land, they disperse up the flyways. The sheer random chance of

inhabiting the same 20’ square space as any given warbler would be miniscule if

they weren’t coming through in such large numbers.

[viii]

Many bird sanctuaries and parks will maintain small water features that draw

thirsty migrating birds. I have mixed feelings about this as it’s nice to have a known location, but it

also feels a bit like hunting deer at a feeder.

[ix] I

also have to admit that my first “birdwatching trip” of the season was to

Balcones Canyonlands, near Austin, a 6 hour round trip ostensibly for one

single species of bird. This is something I’ve looked askance at in days past.

In my defense, I’ve wanted to hike Balcones for a long time, and was invited by

a colleague. But still, 400 miles for 4 inches of bird. Didn’t even get a good

picture of one.

[x]

Part of that was sheer, stupid luck, and part of it was a function of the

excessive volume of time spent in the field this year.

[xi]

31 species X 5” per bird = 155 inches.

No comments:

Post a Comment