This is the third in a three-part

series of posts about spring bird migration season, 2013. For the overall season

summary click here, and for the second post about warblers, click here. I

promise…no more bird posts for a while.

Unlike a lot of folk who saunter out to

watch birds on a regular basis, I am not a retiree[i]

, so my time in the field is often limited to brief stints on weekends, and

stolen hours on workday lunches. I’ve

never taken a long distance trip solely for avifauna[ii]

or had the luxury of devoting weeks to exploring an area.

However, with fatherhood looming with all of its requisite

duties and obligations in tow, I knew that this migration season would be one

of the last in which I would have a chance to spend liberally of my time. With

the season drawing rapidly to a close, I decided a last hurrah was in order,

and aimed to devote an entire day[iii]

to a long excursion around the Coast. I’ve never contemplated doing a “Big Year”,

in which one rushes to and from to check as many birds off a list as they can

in a year. However, I did like the idea of a Big Day focused on simply

exploring as much as I could in as many places and seeing as much as I could

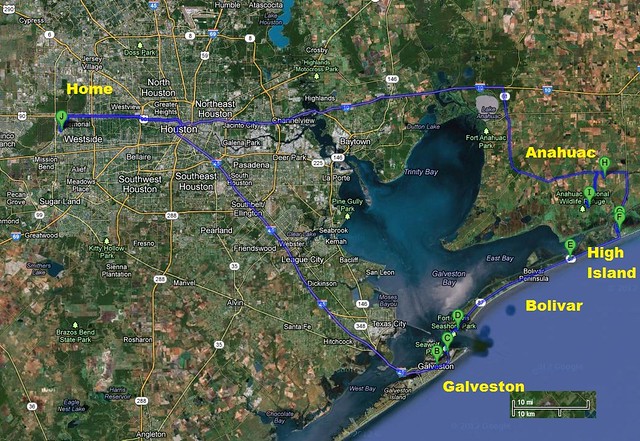

practically hunt down. I decided to

mirror a similar trip I’d taken in coastal lands the year before and make a

grand circumnavigation of Galveston Bay.

It's awesome when your intended route for a day can be seen from space.

To the Coast

To be down on the Coast at sunrise, I heaved my weary self

out of bed at a dark and bleary 3:30 AM.

Dragging on some clothes in the dark, I bid goodbye to my wife and

proto-child, received a mumbled response in return that was likely something

along the lines of “what..the hell…is wrong…with you…”, grabbed my gear, and

set off[iv].

I flushed up my first bird of the day, an incredulous Common

Nighthawk, along the road as I left my neighborhood and cruised on down to

Galveston[v].

The 6:00 AM ferry to Bolivar Peninsula that morning was buffeted by cold winds,

so I didn’t get a chance to spend much time on deck as I usually do. Galveston

and Bolivar form the southern arms[vi]

of Galveston Bay, so the ferry ride is a short one across the opening. The usual mix of pelicans, gulls and terns wheeled around the ferry,

but it was too dark to note much else. Still, there’s nothing like the

sight of sunrise over the endless horizon of the Gulf.

Ferry to Bolivar, Dawn over the Gulf,

Birds and Morning Sky Abstract, Morning star

Bolivar Peninsula

Bolivar itself is a mishmash of high end development, utter

ruin, and coastal scrubland (I wrote about it and its trials

and tribulations during Hurricane Ike here.) However, its assorted habitats

are perfect for a variety of birdlife. At the mouth of the bay, a 5 kilometer

jetty strikes out deep into the Gulf to prevent sediment from closing the Bay opening. It creates behind it mudflats, lagoons, and beaches that

are great habitat for wildlife. The jetty was my first Bolivar stop, still wreathed in the blueblack cold of daybreak. The sun had just begun to burn its way through

the containing line of the horizon, turning the thin sheen of water on the

mudflats into molten gold. Identification of anything silhouetted by that

inferno was near impossible, so I had the rare opportunity to sit back and

enjoy the scenery as a whole on a bird trip.

Bolivar Peninsula

Daybreak over Bolivar

Flats, Flocks at Dawn, Sea of Gold, Sunrise Video, Sunrise Panoramic

Audubon maintains the massive tract of mudflats and

beachland behind the jetty as a shorebird sanctuary, and it is aptly named. The

shallow flats and sandbars support a teeming multitude of sandpipers and

plovers, as well as larger wading birds. Unlike most beaches in the area,

driving on the beach within the Sanctuary is not permitted, so one gets the

rare treat of a beachscape undisturbed but by tide and the occasional hiker. I

drove down the shore to the sanctuary, and then made my way out to a sandbar

and ate breakfast as the sun rose over the Gulf and curious birds skittered

around me. In the early light, the Flats looked like a living, undulating thing from the motion

of the thousands of peeps running this way and that.

Semiplamated Plover in

Ripples, Shorebirds, Willet

A Peregrine Falcon coursed over the

grassy marsh, and a small circle of Pelicans held court on a high spot in the

mudflats, surrounded by a coterie of thousands of assorted shorebirds circling

around them in a great swathe. Large flocks of Black Skimmers lifted up on my

approach, gliding past and around me almost silently despite the size of their

group.

Kingdom of the Pelicans,

Black Skimmers in Flight, Sandwich terns, Short-billed Dowitchers, Black-necked

Stilt

The sun rising in the sky meant time was running short for

the morning, so I picked my way back along the dune line of the beach to my car

and set out down the Peninsula’s length.

Wilson’s Plover on the

Dunes, Uncommon Morninghawk, Ripples in the Sandbar

However, a kolache[vii]

shop along the way convinced me that my healthy breakfast on the beach, though

beautiful in scenery, was meager in road-trippy goodness. I allowed myself to

be waylaid briefly for some additional Texas fare.

Yum.

I popped by various other points on the Peninsula, searching

its back bays and interior fields and wetlands, but found only ruined

foundations, abandoned boats, and trash. At Rollover Pass, where the Peninsula is

sundered from the mainland, birds were scarce. I did score a “lifer”, the

comically designed American Oystercatcher. Early fisherman had scared most of

the rest of the flocks off, and my excitement at a new species was tempered

somewhat by a reluctant but necessary encounter with perhaps the most ruinous,

festering port-a-potty known to man[viii].

Not wanting to waste anymore precious

morning light/time, I booked on down the Peninsula to High Island.

American Oystercatchers

are from the Platypus school of design

High Island

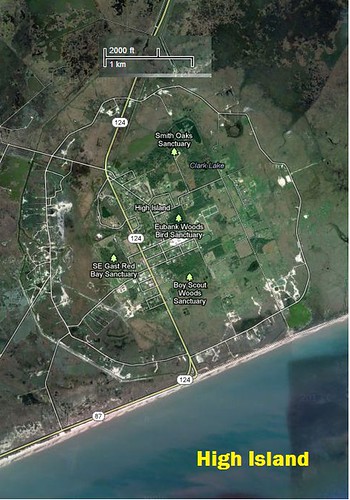

High Island is a Mecca[ix]

of sorts for the birdwatching community during migration. It’s essentially a town

built on a salt dome, making it the highest[x]

point on the coast. What makes it of any

note is its small stands of forest are the only game in town for birds who have

just flown day and night over the Gulf. Migrant drop out here to rest and refuel,

especially when flying into northerly headwinds. Nothing causes more excitement

during migration season than the potential for one of these “fallouts”, and

conditions were right that morning[xi].

Because of this geographical serendipity, Houston Audubon maintains a series of

wooded sanctuaries around the town[xii].

My first stop was at Boy Scout Woods, a

small forested tract that is a first stopover for many migrants.

High Island. The outer road

encircling the town shows a rough outline of the salt dome.

There were dozens of birders at BSW, and I think I brought

the average age down by a decade or two. One of the usual activities at these

locations is to sit (here on bleachers) and wait patiently for birds to come to

a water feature 50 feet away. Not my cup of tea. I roved around for a while,

catching some great birds in a nearby stand of bottlebrush. The word was going

around that there were a great number of birds at Smith Oaks, the largest of

the High Island Sanctuaries, so off I went.

High Island Landscape, Boy Scout Woods, Bottlebrush, Western

Tanager

In retrospect I should

have probably gone straight there in the morning, but it was still pretty

active when I got there. As soon as I got out of my car, the species list for

the day started growing exponentially. Several older birdwatchers were camped

out at a seeming nondescript spot between woods and lake. As I was talking with

them, a flurry of warblers swarmed around me. The lingering winds from the

fallout conditions had driven a large multitude of the birds to the shoreline

of this small lake and adjacent woods, creating and ideal migrant trap. I spent

the next hour or so hardly moving as species after species flitted by, past, or

onto me in a great swarm. While I was

there, I realized my life species count was 349…1 short of my original goal of

350. As I sat there in swarms of more common birds, a female Cerulean Warbler,

my long time nemesis[xiii],

popped out from the underbrush and posed briefly for picture. Number 350, check.

Smith Oaks, Oaks Path, Cerulean Warbler (f),

Blackburnian Warbler (f), Black-and-White Warbler, Chestnut-sided Warbler,

Vireo

Unlike other trips, the winds kept things fairly cool and

mosquito-free…an almost unheard of phenomenon in the tropical sauna that is usually

the Upper Texas Gulf Coast in May. The paths were practically dripping with

warblers, vireos, and other migrants. I walked through the wetlands, and

majestic old oak mottes of the sanctuary and took a quick swing by the rookery.

Surrounded by a manmade lake, a series of small islands supports a massive

rookery area at Smith Oaks, with a constant ear-shattering roar of Egrets,

Herons, Spoonbills, and other colonial birds conglomerated over a massive

bramble of nests and breeding grounds. Even more surreal is the underlying bass

laid down by cormorants, croaking like Tuban throat-singers. While the migrants

drive the crowds to High Island, the rookery spectacle is what always impresses

me the most.

Roseate Spoonbill, Egret Chicks, Snowy Egret, Rookery Video

The rest of the day dissolved into continuous hiking and

exploration of Smith Oaks, and a late afternoon flurry of warblers. I

reluctantly left the Sanctuary a little after 4 PM. Of the 38 or so warblers

one could potentially see in a season on the UTC, I had found at Smith Oaks

26 in one day, in one place[xiv].

Canada Warbler, Magnolia

Warbler, Golden-winged Warbler, Tennessee Warbler, Black-and-white Warbler Video

Anahuac

On the return portion of my loop around Galveston Bay, I

stopped by the decidedly different terrain of Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge.

Anahuac is a great big sea of flat. Tall marsh grasses enclosed only by levee

roads with almost no trees anywhere. It’s a place of alligators and old oil

drilling sites, but not much else except a relatively abundant diversity of marsh

birds[xv].

The light was fading a bit so I took a couple quick turns around the main

basins, but didn’t turn up much more than a couple annual looks at some coastal

species. Still, the different habitat added several more species on the day,

even if they weren’t terribly exciting.

Flatlands, All Along the Watch Tower, Least Bittern Up, Least

Bittern Down

The Road Home

At 7 PM, with the light dying slowly in a murky miasma on

the horizon, I set back on the long road to the freeway home. As I was passing

through some agricultural fields[xvi],

I noticed a great roiling cloud of dust headed my way. I pulled over as the

dust cloud passed me by. As it began to clear and light rays scattered through

the premature dusk, I noticed one, then two, then a dozen, then a multitude of

motionless hawks all around me. Some perched on fences, some stood on the

ground, some peered from the underbrush. The gathering of raptors became clear

when I saw that the source of the dust was a farmer plowing up a vast overgrown

field. Rodents in the vegetation fled in the wake of the tiller, onto the dry

bare ground, where they were a helpless feast for the hawks. I saw almost all

of the expected raptors for the day all at once. It was a fantastic way to end

the day.

Swainson’s Hawk on

Fenceline, Swainson’s Hawk on Ground, Swainson’s Hawk

Results

While it wasn’t completely the intention, this “Big Day” was

a pretty damn good last hurrah not only for the season, but for the foreseeable

future. I found over 140 bird species

in one day, 26 of which were warblers. Even though I hadn’t set out to run up a

huge tally, it spoke well of the extent of the day, and the scope of the sojourning

through different places. Fittingly, on what was likely my last long day of

birding for a while, I finally found my 350th species, fulfilling

the original goal I’d set for myself when I started off down the path of

learning the area birds. Even more fittingly, that 350th species was

my old nemesis, the Cerulean Warbler. When I pulled back into my driveway that

evening, it was 9:30. 220 miles and 18 solid hours

of excursion lay behind me, and the challenges of fatherhood lay before me. I’m

not looking backwards.

Black Skimmers in Flight

NOTES

[i]

Though I have enough grey/missing hair to pass as one these days.

[ii]

Unlike some of my colleagues who regularly travel the globe specifically for

birding. I fit mine in where time on vacations permits. I certainly don’t look

askance at bird-related travel. I just don’t have the time or vacation to do

it, nor do I think I could narrow my focus enough to build a trip solely on one

aspect of nature. This translates into a lot of early mornings before the rest

of the family awakens.

[iii]

So sad that a single day seems such a dear and inordinate amount of time. I remember

glorious expanses of time as a kid, vast, golden afternoons sacrificed to

wandering without a worry about other commitments. I know some folks who can

still harness that mindset, and I envy them unrelentingly.

[iv] There

is absolutely no greater travel feeling than the first step out the door, with

the vast expanse of your experience-to-be laid out before you, cresting over the

precipice of anticipation. These are the sort of semi-poetic, semi-insane

thoughts that pour through one’s head at 3 AM in the morning, when what you

really should be thinking is, “hey, did I forget the sunscreen?”.

[vi]

Galveston is called an Island, and Bolivar a Peninsula, but both are

essentially part of the long barrier island system that runs along the Texas

Coast. Viva la difference.

[vii]

Kolaches are a universal breakfast food in Texas, harkening back to the German/Czech

origins of the area. They’re really not that amazing to describe…essentially

various fruit danishes and pigs-in-blankets style meat/cheese/etc baked goods.

But with a side of chocolate milk, a couple Jalapeno-sausage-and cheese

kolaches and one or two sweet fruit kolaches will keep you running most of the

day.

[viii]

I’m convinced that it was a direct portal into a previously undescribed ring of

Dante’s hell. Perhaps punishment for those who balk at government spending on

proper utility infrastructure…

[ix] I

do not believe this comparison to overstate the relative zeal of the “pilgrims”

to High Island.

[x] This

is an incredibly relative use of the term “highest”. Also ”town”.

[xi] Conditions

were right to see birds; not great for the birds themselves. Birdwatchers love

fallouts, but it’s a mixed bag because strong northerly winds that ground birds

on the coast essentially mean that mortality in the migrating species is going

to go up appreciably as many don’t make it to the coast in the first place. It’s

almost a selfish sort of excitement, and makes me feel a little uneasy in the

extent to which people sometimes turn a blind eye to the consequences of the

phenomenon.

[xii] The

attendees of which, especially in migration season, make up an appreciable

portion of the town revenue.

[xiii]

Yes it is possible to have a 5-inch nemesis. Until this point, the Cerulean

warbler had been the one warbler species that seemed to always appear where I

had just been, or was going to go, but never when I was there.

[xiv] All

in all, as I posted about previously, I found 31 of the ~35 warbler species

over the course of the season. 1 of the missing species was too far afield to

go after, and the remaining trinity were exceptionally hard finds this

season.

[xv]

Like many coastal refuges, it primarily serves to protect wintering grounds for

the large numbers of geese and other waterfowl that flow into it each winter.

[xvi]

This part of the area is deeply, deeply rural. And flat. Think Mississippi

Delta.